Sunday Magazine

Daily Times

How can women in this generation be role models for future generations?

My generation of 50-something’s have a responsibility to lead, and that means mentoring as well as sharing of time. Since time is now the only real currency and can be resourced by all, how we use it matters most. Living by example is one way forward, of course, but that’s still a low bar for me. It’s crucial to define paths to women taking their power, whatever work they do. Take your power, girls – no one is going to give it to you. I believe I try to live that message. I hope my voice and my choices, give some courage and hope to those with less opportunity. I always say never just seek equality, look for more than that, push yourself.

What are some decisions you’ve made in your life that took the most amount of courage?

I don’t like to valourise myself, so perhaps this is a question best left for my memoirs, if I ever get to write them, or for other people to recount. Suffice it to say I have had very few ordinary days, and courage is part of the territory many of us have chosen.

To you, who are the biggest champions of women’s rights in Pakistan?

It is the women who do not have an opportunity to access an education, who do not have the resources middle class women do, but still power on. There is a long list I am compiling. Pakistani women are brave beyond belief, but among the privileged women, I have never met a woman like Benazir Bhutto, who went straight to her death facing the sun, standing up for her followers and her moral universe. She knew she was a target 24/7, she knew after the October 18th explosion in 2007 what limits her campaigning for change, against terrorism and extremism, meant in terms of costs. But she was willing to pay that price, if it meant that her people would not be left alone in a fight to the death. So, her spirit and profile in ultimate courage lives on. As a Prime Minister and leader, she actually stood by the women of Pakistan in more ways than I can re-count here. She was the force that moved a million women to empower themselves, and to imagine a different future.

Who are the most pro-women men you know?

Off the top of my head, my husband Nadeem Hussain, who creates enabling conditions for women at work and believes very seriously in affirmative action. Not to mention his ability to survive more than 16 years in a marriage with me despite tough choices I made, and continue to make! He is probably the most supportive man in the world I have met. Of course, people I work with in the PPP such as former President Zardari, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, and even some PPP parliamentarians make the cut. President Zardari would always respond to my calls on how women are being kept out of decision-making in government or even when the BISP was being created. He made sure the recipients were women when others in the bureaucracy resisted. I can cite many more examples, but this is not the place. Hameed Haroon is another unambiguously pro-woman man. He gave me my first break in journalism and always prefers to hire a woman if her merit equals that of a man on the list of candidates for a job. I am still testing younger men at work that I encounter, so lets see how this list grows by my rigorous standards. Lets see how they enact “HeForShe” in their own lives, and with their own wives!

Most women in politics come under the pressure of covering their head. Did you ever feel that? Why did you choose not to?

Many of us face that pressure in the growing everyday extremisms we see in Pakistani public life. I see it as a personal choice that I have been wedded to for too long. In politics one has to compromise on short-term goals so often in order to attain the achievable big picture that this is one thing I don’t like to change. I am also not terribly good at erasing red lines I once drew, which would have prevented me resigning my cabinet positions, for instance, so this level of clarity bogs me a little in my career am afraid, but I have to live with myself too. For me, the personal has always been the political, and it is part of those choices I have made, just like not changing my last name to my husband’s. I also don’t like to be told there is no choice, or use that moniker too often to justify slippery-slope decisions. There is pretty much always a choice, even if it means leaving your comfort zone, or facing dangerous odds. But there is always a choice, which means one should take responsibility for one’s actions and choices. Sometimes one just has to woman-up and tell truth not just to power, but to oneself. That means you say ‘I did not do this because I needed to stay alive to fight another day,’ or ‘made a choice because I knew I couldn’t live with myself if I did not, despite the deathly odds,’ because that too is a choice.

What quality of yours do you see in your daughter?

My daughter Marvi is still as thin-skinned as I used to be at her age. We have much in common, including a love for animals, particularly dogs. She has an amazing sense of humour, which I like to take credit for, but am afraid she is ahead of me in the one-liner witticism game. She loves to write, like I do, and does it well. I love art as much as her, but she has the patience to hone her amazing talent to a skill, which I did not have as a graduate. I envy her ability to paint.

How different was the landscape for women in journalism in Pakistan when you first started your career and now?

Women were never big players in English journalism even in 1979 when I first landed myself in the Dawn group’s offices. But by and large in the Urdu mainstream press, of course they were restricted to social, fashion and society, or maximum, art reporting. Today that has changed, along with the media landscape itself. For instance, despite my interest in style, which is not the same thing as fashion at all of course, I never touched the fashion section in the Herald magazine that I edited, because I consciously charted a path for myself as a mainstream journalist, and didn’t want to be ghetto-ised in what were known as women’s pages or duties in those days. I did however, always add a feminist or rights components to any newspaper I was involved with.

In your opinion, how do women connect with Khaadi? What makes Khaadi the “preferred” Pakistani brand?

I can only speak to how I connect with Khaadi, and that is based on its strong Pakistani design aesthetic rooted in layers of a multicultural and inclusive design idiom. If you look at Khaadi as an experience, not just as an outlet that sells a series of pret outfits or unstitched fabric, you can see that it takes a very post-colonial art-house view of the creative universe, and it totally stays on the cutting edge. It is not tone-deaf, shall I say, to the colour palette of change, but stays rooted in a strong original, very indiginous design vernacular, with a robust nod to South and Central Asian motifs resonating in global design outputs. To my limited shopping experience, it’s the first mass-retail brand that is both very Pakistani in its local idiom, and yet resonates with a very modern, very global vibe. It picks up the street pulse as well as the international design trends in its design articulation, even its store windows. Of course, its initial, 18th century and even earlier symbolic use of the Mughal paisley and poppy design perennials were a signature draw for me, as only niche block-makers and designers were doing that. Khaadi made Pakistan’s strong cultural tradecraft in its historical authenticity, including use of colour, dyes and motif, go retail-viral. My compliments to Shamoon and his team. I hope they can expand to stores all over the world. They make Pakistan proud.

INTERVIEW: Anusha Bawany

PHOTOGRAPHY: Nefer Sehgal

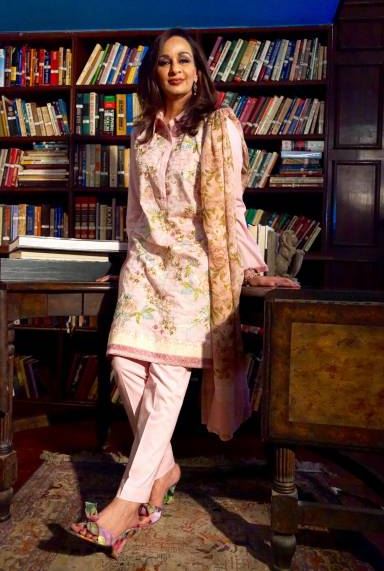

WARDROBE: Khaadi